The Fourth Years of Taliban's Rule in Afghanistan – Where Suppression Stands?

Executive Summary

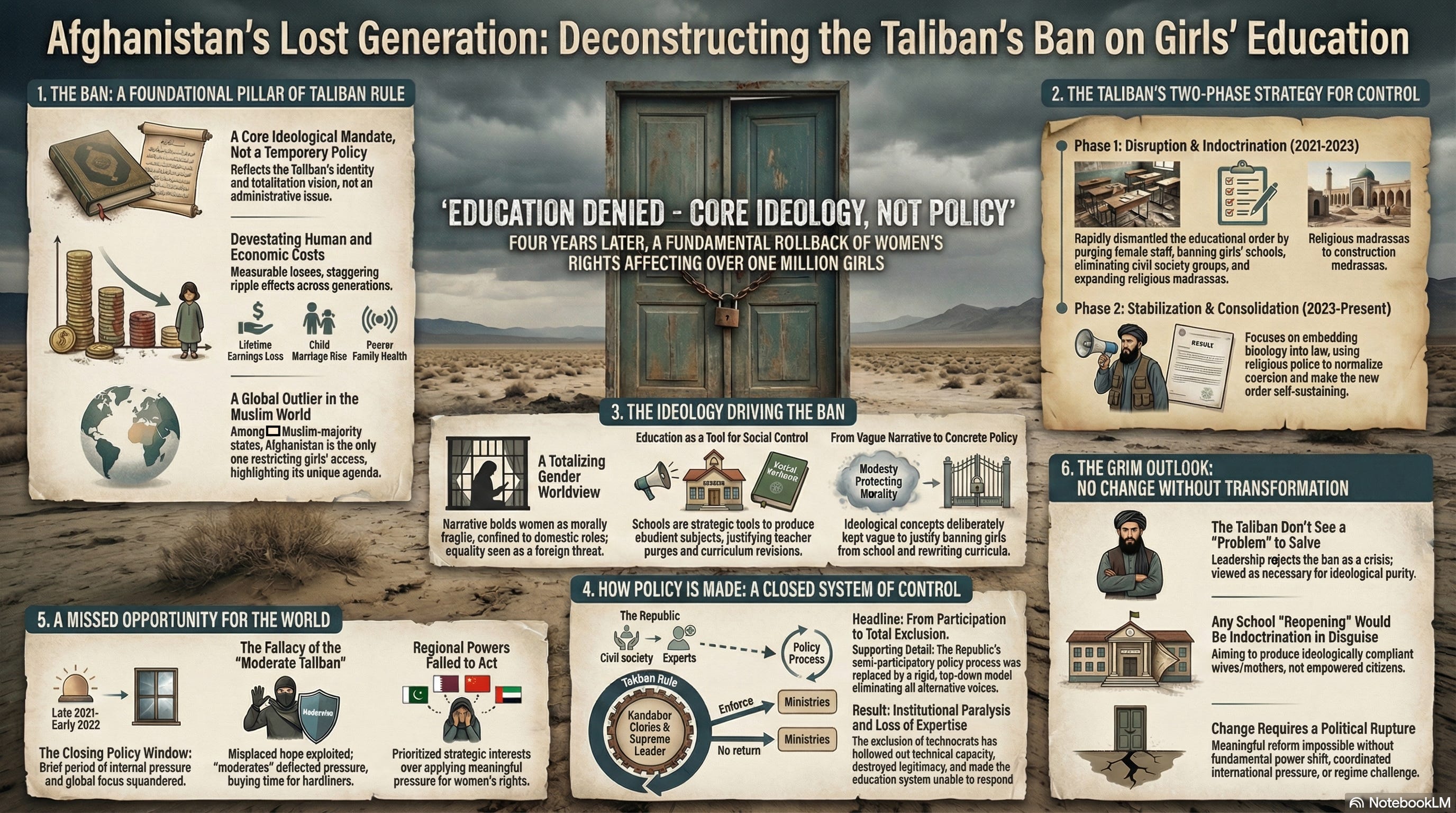

Approximately four years after the collapse of the Republic, Afghanistan is witnessing a significant regression in the rights of women and girls, marking a troubling chapter in its modern history. The Taliban’s prohibition of secondary and higher education for girls, initially framed as a temporary measure due to concerns about dress codes, has now become a foundational element of their ideological identity. Despite previous promises of potential reconsideration, no advancements have been made. Instead, the Taliban have deepened their totalitarian regime through legal frameworks, institutional changes, and moral surveillance.

This situation should not be seen as merely an administrative issue; it is a deliberate reflection of the Taliban’s political ideology, which rejects gender equality, confines women to domestic roles, and views education as a tool for ideological reinforcement. As long as this mindset prevails among the leadership—particularly their so-called Supreme Leader and the Kandahar clerical circle—girls’ education will remain incompatible with the regime’s governing principles.

International and regional stakeholders missed a critical opportunity early in the Taliban’s rule when internal dissent, global scrutiny, and political uncertainty briefly converged. A misplaced belief in narratives of a “moderate Taliban” and fragmented diplomatic efforts enabled the regime to delay, deflect, and ultimately entrench its position.

The potential for reopening girls’ schools on a large scale now depends on political transformation. Achieving this change will require adjustments in the Taliban’s internal power dynamics, shifts in their ideology through coordinated international pressure with tangible consequences, and broader societal changes. Without such transformations, the ban on girls’ education will remain a deeply rooted aspect of the Taliban’s ideological framework, hindering Afghanistan’s human capital, economic development, and social justice for generations.

Part 1: The Years of Suppression & Abuse

A troubling image persists: Afghanistan’s once-vibrant schools, filled with girls and women actively participating in public life, now stand silent under the Taliban’s strict rule. The change was swift and devastating. Within weeks of taking power, the Taliban closed nearly all secondary schools for girls, affecting over one million girls who had completed primary education or were already in higher grades. This setback is not merely a policy error or a temporary pause; it clearly indicates that the Taliban never supported equal educational rights. Their focus remains ideological rather than national.

The implications of this ban extend far beyond closed school doors. Denying education results in significant losses in lifetime earnings, undermining household resilience and national economic prospects. Research consistently shows that educated women make informed health choices, leading to lower child mortality rates and improved family well-being. Recent reports indicate a rise in child marriage since the ban, underscoring how the lack of education fuels gender-based violence and entrenched poverty. The human cost is immense, with repercussions that will affect generations.

When the Taliban enacted the ban in 2021, they claimed it was temporary, stating that existing school arrangements violated “religious and traditional values.” However, these values were never clearly defined and shifted in meaning when challenged. In truth, the Taliban’s stance is grounded in their ideological beliefs rather than a reflection of Afghan religious or cultural consensus. If they were transparent, they would acknowledge that education for girls beyond primary level contradicts their doctrine, not Afghanistan’s heritage.

Education is deeply intertwined with ideology and politics, and in Afghanistan, this connection is more evident than ever. Public education mirrors political power: who controls funding, sets curricula, and governs access. Although private education relies less on public financing, it remains subject to state regulation and ideological expectations. This reflects global trends, but under the Taliban, this relationship is pronounced and rooted in a totalizing political agenda.

At its core, the Taliban regime embodies totalitarian governance: consolidating power, enforcing a singular ideology, and stifling dissent. In such a system, education is not viewed as a public good but as a strategic instrument for social control, ideological reinforcement, and regime consolidation. Schools must cater to the state rather than the nation; they are expected to produce compliant subjects rather than critical thinkers. This explains the Taliban’s priorities: expanding madrassas, revising curricula, purging teachers, and enforcing gender segregation, while dismantling mechanisms that foster open discourse or participatory policymaking.

The Taliban’s governance agenda aims to establish a new social and political order—one that negates the achievements of the past century and reinstates a rigid societal structure briefly attempted in 1929. Under this vision, educational policy serves as a primary vehicle for entrenching ideological authority.

The Taliban’s ideological aggression since their return to power reveals a calculated strategy of disruption followed by consolidation. Their initial phase, characterized by sweeping bans and institutional dismantling, eliminated competing sources of authority—civil society organizations, tribal institutions, women’s movements, teachers’ associations, and human rights groups—that once influenced the educational landscape. The current phase seeks to normalize and solidify this order through legal codification, strict enforcement, and a bureaucratic structure that ensures ideological compliance at every level.

The outcome is a society where education is no longer a means of empowerment but a tool for fostering ideological conformity and promoting violence, posing a threat not just to Afghanistan but beyond.

Part 2: The Taliban’s Policy Framework

The Taliban’s education policy over the past four years demonstrates a unified ideological agenda rather than a collection of separate administrative actions. At the core of this agenda is the belief among the movement’s senior leadership that the educational system established during the Republic produced a workforce shaped by secular, liberal, and democratic values, which fundamentally contradict their worldview.

This ideological perspective plays a crucial role in their decision-making. Senior leaders, including their Supreme Leader, Haibatullah Akhundzada, along with key figures like Minister of Higher Education Nida Mohammad Nadeem, have publicly committed to preventing girls from returning to secondary schools and universities. For boys and young men, they promote what they call “re-education,” aimed at eliminating “Western” influences and instilling Taliban doctrine.

Public statements over the last four years highlight the strength of this ideological commitment. At a madrassa graduation in January 2024, Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi—often perceived externally as a “moderate”—accused Afghan youth of being “brainwashed” by Western ideas and stressed the need for their reintegration into an Islamic worldview as defined by the Taliban. The Minister of Higher Education supported this view, stating that the Taliban-led education system has a responsibility to “correct” the thinking of students influenced by the Republic. These statements clearly reflect a policy objective: to transform schools and universities into instruments of ideological instruction rather than centers for knowledge and public development.

This ideological agenda has unfolded in two distinct phases. From the perspective of punctuated equilibrium theory, the Taliban’s approach can be seen in two distinct streams. First, they initiate a period of aggressive disruption to displace the previous equilibrium and normalize a new ideological structure. Second, once this disruption has settled, they gradually expand institutional changes, ensuring that ideological enforcement becomes deeply entrenched and less reliant on overt coercion.

Phase One: Disruption and Indoctrination (2021–2023)

The Taliban’s initial strategy focused on rapidly disrupting the education system established by the Republic. This phase can be characterized as a “shock stage,” defined by swift institutional changes aimed at dismantling existing frameworks.

Key aspects of this phase included:

A nationwide ban on girls’ education beyond primary level, which not only removed a fundamental right but also reduced the perceived social and economic value of women’s education.

Purges of female teachers, administrators, and university staff, along with the intimidation or removal of educators deemed “ideologically unsuitable.”

Accelerated madrassa expansion, aimed at replacing or overshadowing general education with religious schooling under Taliban control.

Curriculum revisions, introducing religious content while eliminating subjects viewed as inappropriate or “Western.”

The reintroduction of corporal punishment, indicating an authoritarian approach to socialization and discipline.

Despite internal disagreements among Taliban officials—some advocating for a more gradual approach to avoid public backlash—the more radical faction prevailed, emphasizing immediate structural and ideological changes. This resulted in a policy environment marked by coercion, exclusion, and ideological imposition.

Phase Two: Stabilization and Consolidation (2023–Present)

The Taliban have entered a second phase characterized by the consolidation of an ideologically exclusive order. This phase emphasizes embedding, enforcing, and normalizing the previously established ideological agenda rather than introducing new policies.

A key aspect of this phase is the formalization of ideological control through codified instruments. The Law on the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice illustrates the Taliban’s intentions, effectively marginalizing women from public life and empowering the religious police to enforce “moral order” in both public and private spheres.

This stage aligns with what policy theorists refer to as a policy consolidation period, where the introduction of new regulations slows down, but enforcement becomes more stringent. The Taliban are converting their ideological preferences into binding legal norms, framing them as the legitimate legal and moral foundation of the state.

The shift is also apparent in institutional behavior. Ministries are undergoing ideological vetting, and adherence to Taliban directives is enforced through bureaucratic and coercive measures. For example, the Ministry of Higher Education has removed all images of living beings from its website and ceased public visual representation. In regions like Kandahar, universities have even banned mobile phones on campus, deeming them tools of moral corruption.

This phase is not just about strict enforcement; it also seeks to create a perception of normalcy. By normalizing coercion and integrating ideological control into daily governance practices, the Taliban aim to establish a self-sustaining system where deviation is socially unacceptable and structurally unfeasible.

Throughout both phases, one principle remains constant: education is the frontline of ideological control. The Taliban’s policies demonstrate a steadfast commitment to transforming Afghanistan’s educational landscape into a mechanism for sustaining their totalitarian vision of society.

Part 3: Narrative & Policy

The Taliban’s approach to education is fundamentally shaped by their ideological narrative, developed over the last thirty years. This narrative blends anti-modern education sentiments, selective religious interpretations, and propaganda from the insurgency era, influencing the content, execution, and rationale behind their educational policies. It serves not merely as rhetoric but as a governing doctrine that informs their decision-making.

The Construction of an Anti-Modern Educational Narrative

The Taliban did not merely foster skepticism towards modern education; they radcialized it. They capitalized on existing concerns among religious extremists regarding modern institutions within Afghan society, despite ongoing public support, and reframed these concerns through a rigid ideological perspective unprecedented in the country’s educational history. According to their viewpoint, modern education is seen as corrupt, Westernized, morally hazardous, and incompatible with an “authentic” Afghan-Islamic identity.

Over time, the Taliban institutionalized this perspective through various means:

Religious narratives, selectively interpreted to justify gender segregation and the subjugation of women.

Insurgency propaganda, including chants, anthems, and battlefield songs that glorified jihad while denouncing modern schools as centers of moral decline.

Local messaging networks, comprising madrassa preachers and front-line fighters, who disseminated simplified concepts regarding gender, morality, and the perceived threats of “Western thinking.”

This established a robust ideological ecosystem: a multi-layered network of clerics, commanders, loyalists, and ultra-conservative community members who absorbed and perpetuated Taliban narratives without question. This decentralized yet coherent system enabled the Taliban to sustain a unified ideological message even in the absence of a formal ministry or structured hierarchy during the insurgency.

Narrative Meets State Power

During their insurgency, these narratives had limited practical application; they were more aspirational than actionable. However, after the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in 2021, the ideological framework gained significant weight. What was once rhetoric transformed into governing policy.

The Taliban’s educational narrative is now evident through:

The ban on girls’ education beyond primary school

Curriculum revisions that emphasize obedience, religious texts, and moral policing

Restrictions on subjects considered “Western” (civics, arts, music, social sciences)

The dismissal of women teachers and administrators from schools and universities.

The expansion of madrassas as preferred learning institutions

Even laws that do not explicitly address education—such as the Law on the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice—play a role in shaping the social environment necessary for enforcing these educational policies. They limit women’s public presence, justify moral oversight, and foster a cultural climate where educational deprivation is normalized.

From Narrative to Policy

The Taliban’s narrative not only justifies policy but also shapes educational policy based on their radical moral interpretation. A clear example of this is their discourse surrounding ḥayā (modesty) and “protecting morality.” These intentionally vague terms serve as the foundation for specific policies, such as banning girls from secondary and higher education, removing women from classrooms, segregating students, rewriting curricula, and restructuring schools to prioritize obedience over inquiry.

What starts as an ideological assertion transforms into an administrative directive.

The Gendered Foundations of the Taliban’s Narrative

At the core of this ideology is a rigid gender perspective. Within the Taliban’s framework:

Women are viewed as inherently morally fragile and are relegated to domestic roles.

Girls are seen as needing “protection” from social exposure, public knowledge, and modern influences.

Education for girls is acceptable only if it prepares them for motherhood and domestic duties.

Men alone hold public authority, religious autonomy, and interpretive power.

This worldview is not merely patriarchal; it is totalizing. It frames women’s exclusion from public education not as a social choice but as a divinely mandated reality. In this context, gender equality is not just dismissed; it is perceived as a threat to the moral order and the legitimacy of the state.

The Ecosystem of Narrative Production

The Taliban’s narrative is not solely shaped by senior clerics or political leaders; it arises from a distributed ideological network that includes:

religious authorities who approve and share doctrinal interpretations;

madrassa teachers who incorporate these ideas into their lessons;

members who enforce these beliefs through coercion;

conservative community members who socially validate them;

illiterate or semi-literate supporters who accept them as unquestioned truths, as they represent their primary source of information.

These groups constitute a small fraction of the Afghan population, likely less than 10%. This diffusion contributes to the narrative’s resilience, as it is continually reiterated, re-legitimated, and integrated into daily social life. It is neither accidental nor temporary; rather, it serves as a strategic foundation for governance.

Narrative as a Policy Tool

The Taliban utilize narrative to obscure the contradictions and shortcomings of their policies. When their previous justifications—such as dress codes, co-education, and curriculum issues—became challenging to uphold, they pivoted to new arguments, including women’s “safety” or “honor.” This flexibility in narrative enables the Taliban to maintain policies lacking religious consensus, cultural legitimacy, and historical precedent in the Muslim world.

Over time, the narrative becomes the policy, and the policy becomes the narrative.

Ideology Made Visible

The connection between narrative and policy is a hallmark of the Taliban’s governance. Their anti-modern education narrative is not merely an accessory; it is the primary mechanism through which they legitimize state actions, justify repression, and influence the country’s future. By embedding this narrative within administrative frameworks, laws, curricula, and daily life, the Taliban aim to construct a social order that reflects their totalitarian vision.

In this context, schools transform from places of learning into tools for ideological reproduction. The Taliban’s narrative, once limited to insurgency propaganda, has now become the foundation for the state.

Part 4: Taliban & the Policy Process

The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan’s education policymaking represents a fundamental transformation, not just a change in leadership. They have replaced a semi-participatory governance structure with a rigid, top-down model designed to exclude alternative voices and consolidate ideological control. This shift is a deliberate effort to eliminate pluralism in education governance and embed the movement’s worldview into the state’s institutional fabric.

From Semi-Participatory Governance to Total Exclusion

During the Republic, the Ministry of Education’s policymaking environment had weaknesses like politicization, donor dependency, and limited capacity. However, it still had formal and informal avenues for participation. Working groups within the Ministry brought together civil society actors, donor agencies, NGO networks, and experts to contribute to initiatives like girls’ education, emergency responses, quality improvement, curriculum development, and teacher training. These groups were imperfect, but they symbolized a commitment to inclusive governance and pluralistic input.

This architecture has been entirely dismantled under Taliban rule.

The Taliban’s Top-Down, Ideologically Driven Model

Under the Taliban, policymaking is now fully centralized within a narrow elite circle, with the so-called Supreme Leader’s office as the ultimate authority. Ministerial bodies function as instruments of enforcement, not policy innovators or autonomous administrators. The system operates according to several defining features:

1. Concentration of Authority

All significant educational decisions are routed upward, often reaching only a handful of senior clerics in Kandahar. This is ideological centralization, not bureaucratic efficiency.

2. Elimination of Participatory Channels

Civil society organizations, teacher associations, women’s groups, donor agencies, and local communities have been stripped of any role in policy deliberation. Many have been banned or operate under severe restrictions.

3. Ideological Veto Power

Even when bureaucrats or technocrats present pragmatic proposals, the ideological leadership retains veto power. The Supreme Leader’s interpretation of religion functions as the ultimate guiding principle.

4. Coercive Compliance

The policy process relies on coercion rather than consultation. Administrative purges, public punishments, and surveillance ensure that opposition cannot shape policy outcomes.

From the standpoint of elite theory, the Taliban’s governance structure represents an extreme concentration of power in the hands of a small ruling group insulated from public accountability.

Policy Process as Ideological Enforcement

The Taliban’s policy process is not merely centralized; it is instrumentalized. Procedures that once encouraged stakeholder engagement are now designed to ensure ideological conformity. Policy design, implementation, monitoring, and enforcement all follow the same logic:

– Design: Policies must reflect the movement’s doctrinal positions, with religious clerics as the ultimate arbiters.

– Implementation: Provincial and district directorates enforce policies mechanically, with little discretion or interpretation.

– Monitoring: Inspections and enforcement are carried out by religious police, Taliban-appointed committees, and intelligence units.

– Accountability: Sanctions, dismissals, and detentions replace professional evaluations or performance-based assessments.

This approach collapses the distinction between policy and ideology. In effect, policymaking becomes a process of translating the Taliban’s worldview into state practice.

From Policy Deliberation to Policy Domination

The exclusion of alternative actors is strategic. Civil society, especially women’s groups and human rights organizations, once acted as critical safeguards for educational equity. Their elimination ensures that no counter-narratives or reform pressures can infiltrate the policy arena.

The Taliban’s domination of the policy process reflects a broader political strategy:

– control discourse

– control policy

– control institutions

– control society

This sequence reinforces the movement’s totalitarian character, in which the state and ideology become indistinguishable.

Implications for Education Governance

The Taliban’s capture and redesign of the education policy process has profound implications:

Loss of Legitimacy

With the elimination of public consultation, the policymaking process lacks democratic or procedural legitimacy. It reflects the will of the ruling movement, not the needs of the nation.

Loss of Technical Expertise

By removing or intimidating technocrats, the Taliban have hollowed out the technical capacity required for system reform, budgeting, planning, or quality assurance.

Loss of Responsiveness

The system cannot accommodate local needs, regional disparities, or specialized issues because it is rigidly tied to ideological dictates.

Loss of Pluralism

The absence of civil society eliminates alternative perspectives, innovations, and critical checks, weakening the entire governance ecosystem.

Institutional Paralysis

With policy driven by ideological inflexibility rather than evidence, Afghanistan’s education sector becomes incapable of long-term planning or adaptive reform.

Conclusion: A Policy Process Designed for Control, Not Education

The Taliban have replaced a flawed but participatory governance structure with a monolithic, exclusionary model. This policy process is not simply authoritarian—it is totalitarian, engineered to ensure that no dissenting voice can influence educational policy. It transforms the Ministry of Education from a national institution into an apparatus of ideological enforcement.

Under this system, policymaking is no longer a forum for problem-solving. It is a mechanism for reproducing the Taliban’s worldview. And education becomes the primary arena in which this worldview is imposed.

Part 5: Strategic Phases of Taliban Consolidation and Policy Implementation

Understanding Taliban governance requires recognizing that their approach to education is not accidental, reactive, or improvised. It is a strategically sequenced political project aimed at reshaping the social order, consolidating authority, and embedding ideological control across institutions. Since 2021, this project has unfolded in two distinct but interconnected phases: initial consolidation and ideological stabilization. Together, they reveal a deliberate attempt to transform Afghanistan’s educational ecosystem into an instrument of totalitarian governance.

Phase One: Consolidation Through Control, Coercion, and Institutional Overhaul

In the first years following their return to power, the Taliban pursued an aggressive strategy to dismantle the existing educational order and neutralize actors capable of mobilizing opposition. This period—best understood as an attempt to establish governance dominance—was characterized by four major developments:

1. Concentration of Power and Elimination of Dissent

The Taliban rapidly centralized decision-making authority, systematically repressing civil society organizations, women’s groups, teacher unions, youth associations, and tribal elders. This crackdown ensured that no competing institution could challenge Taliban authority.

2. Institutional Realignment

The Taliban reoriented the Ministry of Education (MoE) and Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) toward the movement’s ideological objectives. This involved purging staff associated with the Republic, replacing administrators with loyalists, imposing madrassa-style oversight structures, and reconfiguring school governance to strengthen clerical influence.

3. Legal and Administrative Restructuring

Early decrees and directives laid the groundwork for a new regulatory regime. The Taliban imposed gender bans, dress codes, mobility restrictions, and neo-moral policing practices, creating an administrative environment where compliance was enforced through coercion rather than participation.

4. Suppression of Alternative Narratives

Public expression challenging the Taliban’s educational policies, particularly regarding girls’ education, was criminalized. Activists, academics, journalists, and community leaders faced arrest, intimidation, and exile. As internal pressure built, the Taliban resorted to full censorship, banning discussion of girls’ education altogether.

This first phase established ideological dominance and eliminated the actors necessary for policy contestation, setting the foundation for the second phase, in which the Taliban would transition from dismantling the Republic’s educational order to building and normalizing their own.

Phase Two: Ideological Stabilization and Enforcement (2023–Present)

Having secured institutional control, the Taliban shifted to stabilizing and legitimizing their ideological order. This stage is less about designing new policies and more about routinizing existing ones, embedding them in legal frameworks, and normalizing the Taliban’s vision of society.

1. Legal Codification

The Law on the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice removes women from public spaces, authorizes religious police to enforce moral discipline, legitimizes gender segregation, and normalizes state surveillance in public and private domains. Through legal codification, ideology becomes law, and dissent becomes criminality.

2. Bureaucratic Penetration

The Taliban have embedded ideological supervision throughout all levels of the education bureaucracy, ensuring that educational governance is aligned not with national development needs but with the movement’s doctrinal priorities.

3. Behavioral Normalization

By restricting mobility, censoring public debate, and policing gender interactions, the Taliban have sought to create a social environment in which their ideology feels inevitable. Policies that were once shocking are gradually presented as natural extensions of “Islamic” governance, reducing the need for overt coercion over time.

4. Selective Reinterpretation and Expansion

As stability increases, the Taliban selectively reinterpret aspects of their ideological framework to expand influence where functional gaps remain. This serves to deepen ideological entrenchment and expand the Taliban’s societal reach.

Analytical Perspective: Punctuated Equilibrium and Totalitarian Consolidation

Through the lens of Punctuated Equilibrium Theory, the Taliban’s approach reveals a deliberate two-stage strategy: creating a rupture that dismantles the previous order and installs new ideological structures, followed by consolidation, normalization, and behavioral routinization, making the ideological order durable and self-reinforcing.

Conclusion: An Engineered Social Order

Across its two strategic phases, the Taliban’s policy trajectory demonstrates a coordinated effort to reshape Afghan society through educational control. The shift from shock to stabilization signals the entrenchment of a system designed not to educate but to regulate beliefs, behaviors, gender roles, social expectations, and political loyalties. The Taliban are not merely governing a system; they are re-engineering it. And education—once a tool for national development—is now a mechanism for sustaining authoritarian rule.

Part 6: Prospects for Girls’ Education Under the Taliban Ideological Order

Any analysis of future possibilities for girls’ education under Taliban rule must start with a clear understanding: the current ban is a fundamental part of their ideological project, not a temporary measure. The question is not whether the Taliban will “allow” girls to return to school as they did during the Republic. Instead, the question is whether they will redefine girls’ education to fit their ideological goals while appearing to make concessions.

No Sign of Ideological Change

Despite four years of domestic pressure, international advocacy, and widespread public frustration, the Taliban have given no credible indication that they are willing to revise the core principles guiding their gender ideology. Senior leaders consistently affirm a worldview where:

– gender equality is seen as a foreign idea, – public life belongs to men, – women’s roles are limited to the home, – and education for women is only justified if it supports maternal responsibilities.

Under this doctrine, girls’ education is not a right; it is a conditional privilege granted only when the curriculum, environment, and governance structure align with the Taliban’s ideological vision.

The Myth of “Reopening” Without Reform

Even if the Taliban were to reopen girls’ secondary schools or universities, it would not mean progress toward equality. It would mean the opposite: institutionalizing indoctrination under the guise of education.

Any reopening would be subject to three conditions:

1. Curriculum Control

The curriculum would be revised to emphasize:

– obedience, – religious doctrine aligned with the movement’s interpretation, – moral training, – and gendered socialization.

Critical thinking, civic education, arts, social sciences, and any subject promoting intellectual autonomy would be removed or heavily restricted.

2. Environment Control

Education would be strictly segregated and monitored. Teachers would be vetted for ideological loyalty, classrooms would be watched, and mobility would be tightly regulated.

3. Outcome Control

The goal would not be to empower girls academically or economically but to produce ideologically compliant wives and mothers who can reproduce the Taliban’s worldview within the household.

In this context, schooling becomes an extension of state indoctrination, not a path to social or economic mobility.

Comparative Evidence: The Taliban as an Outlier in the Muslim World

The Taliban claim religious legitimacy for the ban, but their position is unprecedented across the Muslim world. Among 52 Muslim-majority states, none besides Afghanistan under Taliban rule restrict girls’ access to secondary and higher education. Countries like:

– Indonesia,

– Turkey,

– Egypt,

– Jordan,

– Saudi Arabia, and

– Iran (despite its theocratic structure)

not only allow female education but see it as essential to national development, social well-being, and human capability enhancement.

This stark difference highlights a critical point: the Taliban’s stance reflects an ideological agenda unique to their movement, not a theological consensus or cultural norm.

Strategic Reframing: From “Religious Objection” to “Female Safety”

As domestic and international criticism intensified, the Taliban shifted their rationale for the ban. Having failed to justify the policy through religious arguments, they reframed the issue as one of “protecting women” and ensuring “safe” environments.

This shift is revealing:

– it shows ideological rigidity paired with tactical flexibility,

– it masks the lack of doctrinal justification,

– and it repositions the debate from rights to “protection,” sidestepping substantive challenges.

The pattern is clear: when one justification collapses, another is manufactured.

Suppressing Debate and Moral Panic

Starting in 2022, the Taliban banned public discussion of girls’ education and criminalized criticism. Protesters, including women’s groups and youth activists, faced detention, surveillance, and forced disappearance. Civil society organizations were dismantled. Religious scholars who supported girls’ education were silenced.

This censorship serves two purposes:

It shields the leadership from internal challenge.

It constructs a moral panic in which female education is framed as a threat to societal purity.

These tactics reflect the broader strategy of ideological entrenchment: suppress dissent, monopolize interpretation, and criminalize alternatives.

Education as a Tool of Totalitarian Reproduction

The Taliban’s ideological order is built on a totalizing vision of society in which gender roles are fixed, authority is centralized, and obedience is moralized. In such a system, education is not merely regulated; it is weaponized.

The Taliban aim to produce a new generation of Afghans socialized into:

– a binary worldview of “believers” and “non-believers,” – suspicion of modernity, – rejection of global norms, – acceptance of gender hierarchy, – and reverence for the movement as the sole moral authority.

Under these conditions, the exclusion of girls from meaningful education is not a policy mistake—it is a central mechanism for preserving the ideological boundaries of the Taliban’s political order.

Conclusion: No Genuine Prospects Without Ideological Transformation

The possibility of reopening schools, as suggested in periodic Taliban statements, cannot be seen as a sign of reform. It represents conditional access within an unchanged ideological framework. As long as the Taliban’s worldview remains intact, any shift in educational policy will be superficial, tactical, and strategically designed to strengthen regime stability—not to empower Afghan girls.

Real change would require:

– recognition of education as a right, – rejection of gender apartheid, – dismantling of ideological schooling, – restoration of independent institutions, – and reopening of the public sphere.

None of these conditions are compatible with the Taliban’s governing ideology.

Thus, the prospects for girls’ education under the Taliban are not constrained by logistical obstacles or administrative delays—they are constrained by ideology itself. And until ideology shifts, meaningful reform remains impossible.

Part 7: International Missed Opportunities and the Policy Window

The early months of Taliban rule presented a rare policy window, a brief period when internal pressures, global attention, and regime uncertainty aligned to influence the Taliban’s decisions on girls’ education. This window emerged as the Taliban consolidated power, the Afghan public mobilized, and the international community focused on the crisis. However, this opportunity was squandered. Neither regional allies nor global actors applied the necessary pressure to alter the Taliban’s trajectory. This failure reflected structural limitations, misaligned incentives, and misplaced optimism about the so-called “moderate Taliban.”

A Missed Policy Window: Early Internal Pressures and Global Attention

After August 2021, the Taliban faced intense internal and external pressure regarding girls’ education. Families demanded school reopenings, religious scholars supported girls’ education, and localized protests erupted. International organizations and donor countries stressed that reopening schools was a prerequisite for engagement. These pressures combined to create a brief moment when the political, problem, and policy streams overlapped—the exact conditions for opening a policy window. Taliban officials hinted that secondary schools for girls would reopen, but these signals were deceptive, buying time and reducing external scrutiny.

This window rapidly closed as global attention shifted to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Taliban capitalized on this pivot, delaying decisions, issuing contradictory statements, and reversing earlier hints of progress. By the time global attention returned, the window had shut.

Why Regional Powers Failed to Act

Countries with close ties or strategic leverage over the Taliban—Pakistan, Qatar, China, and the UAE—were uniquely positioned to influence the group’s decisions. Yet each failed for reasons tied to its own interests, constraints, and calculations.

Pakistan: Influence Without Will

Despite deep historical ties and substantial leverage, Pakistan opted not to apply meaningful pressure. Its calculus prioritized border stability, countering India, and maintaining influence over the new regime—not supporting Afghan women and girls.

Qatar: Strategic Mediation Without Intervention

Qatar facilitated negotiations and maintained channels of communication with Taliban political actors. However, its diplomatic efforts focused on preserving its role as a neutral mediator rather than pressing hard on specific policy issues. Concerned about jeopardizing its broker position, Qatar remained cautious.

China: Stability Over Rights

China’s engagement centers on security, economic access, and preventing spillover instability. Beijing prioritizes counterterrorism cooperation and protecting regional investments—not shaping domestic Afghan educational policy. As such, it avoided challenging the Taliban directly.

UAE: Recognition Calculus

The UAE engaged the Taliban diplomatically, adopting a pragmatic approach driven by interests in recognition, logistics, and influence. It did not leverage its capacity to condition assistance on changes regarding girls’ education.

Collectively, these actors held the necessary leverage but chose restraint, pragmatism, and strategic ambiguity over principled pressure. This failure contributed directly to the closing of the policy window.

The Fallacy of the “Moderate Taliban”

During this period, a damaging narrative gained traction: that internal factions within the Taliban could be persuaded to support girls’ education. International actors, analysts, and some Afghan elites argued that negotiations should be patient, “moderates” should be empowered, and the Taliban needed time to build internal consensus. This framing reflected a profound misunderstanding of Taliban organizational dynamics. The supposed moderates functioned not as policy reformers but as narrative managers, tasked with softening the group’s image and deflecting pressure.

As during the Doha negotiations, these figures reassured diplomats that reforms were forthcoming, framed the ban as temporary, claimed logistical rather than ideological barriers, and urged patience while the “internal process” unfolded. These assurances created a false sense of progress and encouraged a softer approach among key external actors. Meanwhile, within Afghanistan, they weakened resistance, convincing many that confrontation was unnecessary and that change would happen organically.

The result was disastrous. The so-called moderates did not shift policy. They shifted perception—and bought the radicals time.

Decision-Makers Anchored in Ideology, Not Problem-Solving

Fundamentally, the Taliban’s core leadership operates on ideological imperatives, not pragmatic governance. They seek to shape society according to their doctrinal worldview, not respond to social needs or external expectations. For them, equality is a threat, girls’ education challenges their gender hierarchy, and accepting public demands undermines their authority. Given these priorities, it is unsurprising that the leadership rejected problem framing around girls’ education. From their perspective, the issue is not a policy problem requiring attention but a doctrinal boundary that must be protected.

Thus, external incentives that conflict with ideological interests are dismissed.

Internal and External Pressure: Both in Decline

By 2023, internal dissent had been violently suppressed. Civil society groups were dismantled, protests criminalized, and activists detained. The Taliban employed coercive force to eliminate any domestic actor capable of sustaining pressure.

Externally, pressure waned as geopolitical shifts—including Western fatigue, regional normalization of ties, and strategic recalibrations—reduced Afghanistan’s presence on the international agenda. Countries like China and Russia moved toward recognition, further diminishing the leverage once held by global actors.

In this context, the Taliban faced neither internal nor external forces strong enough to compel change.

A Narrow Political Window—Unlikely but Not Impossible

The only scenario in which change becomes possible is through a shift in the political stream—a fracture among elites, internal power struggles, or a recalibration of the Taliban’s political incentives. However, as long as internal and external conditions align with the Taliban’s ideological agenda, such a window remains deeply improbable.

The leadership does not see girls’ education as a problem. Thus, no solution is considered necessary.

Conclusion: A Case Study in Lost Leverage

The international community’s failure to act decisively during the critical early months—combined with misplaced faith in “moderate Taliban” actors—allowed the leadership to solidify its position. The Taliban successfully closed the policy window by suppressing internal dissent, deflecting external pressure, and spinning narratives that delayed action.

The result is not merely a missed opportunity but a foundational setback for the rights of Afghan women and girls. What might have been a moment of influence has become an era of entrenchment.

Part 8: Explanatory Analysis of Taliban Decision-Making and Ideological Rigidity

Understanding why the Taliban persist in banning girls’ education requires looking beyond surface-level explanations and examining the ideological foundation that shapes their decision-making. The Taliban do not view girls’ education as a governance issue, a policy challenge, or a domain requiring technical reform. Instead, they see it as a core aspect of their identity, a key feature of their political theology, and a test of ideological purity. This worldview makes conventional policymaking logic—based on public demand, evidence, or national interest—irrelevant.

The Leadership’s Strategic Horizon: Ideology Over Governance

At the heart of Taliban decision-making lies a leadership circle tightly centered around the Supreme Leader and his closest clerical advisors. Their strategic orientation prioritizes:

– maintaining ideological coherence,

– upholding internal loyalty,

– asserting the movement’s identity,

– constructing a new social order,

– and consolidating their regime through doctrinal authority.

In this worldview, education is not an administrative sector; it is a political instrument. Girls’ education, in particular, represents a symbolic fault line between the Taliban’s ideological project and the social transformations of the Republic. Allowing it would:

– weaken the ideological boundary between the Taliban and the previous state, – undermine their claim to religious authority, – open space for competing worldviews, – and empower women, thereby challenging patriarchal power structures essential to regime stability.

Thus, from their perspective, conceding on girls’ education is not a policy shift—it is an ideological defeat.

Why the Taliban Reject the Problem Framing

For the international community and Afghan citizens, the closure of girls’ schools is a humanitarian, developmental, and moral crisis. But for the Taliban’s leadership, the issue is framed entirely differently.

They reject the idea that girls’ exclusion constitutes a “problem.” Instead, they interpret:

– public demand as social corruption,

– international pressure as moral interference,

– civil society mobilization as fitna (discord),

– and policy advocacy as Westernization.

From this vantage point, there is no incentive to “solve” the issue. Doing so would require accepting a framing that contradicts their ideological premises.

The Taliban leadership does not acknowledge the ban as harmful. They acknowledge it as necessary.

The Ideological Logic Behind Policy Rejection

Taliban ideology combines:

– a literalist approach to religious texts, – a patriarchal anthropology that assigns fixed gender roles, – a suspicion of modern institutions, – and a belief in religious exclusivism distinguishing “true believers” from “others.”

Within this framework, girls’ education is seen as dangerous because it:

– destabilizes the gender hierarchy, – exposes girls to ideas outside the movement’s control, – disrupts domestic roles critical to their political theology, – and introduces intellectual autonomy incompatible with authoritarian rule.

In short, girls’ education poses an ideological threat. And threats, in the Taliban’s system, must be suppressed—not negotiated.

Why External Pressure Fails

External actors often assume that sanctions, incentives, or diplomatic engagement can shift Taliban policy. This assumption fails because it misunderstands the Taliban’s incentive structure.

For the leadership:

– legitimacy comes from religious narrative, not international recognition,

– power comes from coercion, not public consent,

– success is measured through ideological consistency, not service delivery,

– and political survival requires doctrinal purity, not policy performance.

Thus, incentive-based diplomacy—however rational it appears externally—collides with an internal logic in which ideological compromise is a form of defeat.

The Internal-External Symbiosis of Ideological Rigidity

The Taliban’s ability to maintain ideological rigidity depends on a dual dynamic:

Internal Suppression

Civil society, women’s groups, tribal leaders, and youth activists—actors capable of shaping political incentives—have been repressed, eliminated, or silenced. Without internal contestation, ideological decisions remain unchallenged.

External Ambiguity

As global actors shift toward pragmatic engagement or normalization, the Taliban receive signals—intended or not—that their ideological positions do not endanger their diplomatic standing.

Together, these dynamics create an environment of ideological insulation in which the Taliban face no meaningful pressure forcing them to reconsider their stance.

Four Years of Evidence: Consolidation, Not Concession

Across four years, the Taliban have:

– expanded gender restrictions—not reduced them, – strengthened ideological institutions—not weakened them, – broadened the ban on women—not relaxed it, – intensified censorship—not opened dialogue, – and tightened clerical control over policy—not decentralized it.

This trajectory demonstrates a regime moving deeper into ideological governance, not away from it.

Rather than showing signs of softening, the Taliban have shown a growing inclination to:

– institutionalize gender apartheid, – reshape social order according to their creed, – and align governance with their totalitarian vision.

A Predicted Outcome, Not a Sudden Shock

Some observers described the 2021 school closures as “unexpected.” Yet the trajectory of the Taliban movement—from the 1990s, through their insurgency, to their present rule—consistently points to hostility toward female education. The ban was not sudden, nor was it ambiguous. It was:

– historically grounded, – ideologically coherent, – publicly signaled, – and entirely predictable.

The surprise was not the Taliban’s actions, but the world’s doubt in the evidence.

Conclusion: No Change Without Ideological Shift

The Taliban’s stance on girls’ education is not a policy anomaly; it is a core component of their ideological identity. Without a fundamental transformation in the movement’s political theology, there is no pathway—technical, diplomatic, or economic—that can yield meaningful change.

As long as their identity rests on patriarchal doctrine, religious exclusivism, and totalitarian governance, the ban will remain:

– justified internally,

– defended rhetorically,

– enforced coercively,

– and embedded legally.

Thus, the future of girls’ education under the Taliban hinges not on negotiation or administrative reform but on the question of ideology itself—and whether that ideology can be reshaped, contested, or ultimately displaced.

Part 9: The Taliban’s Expanding Totalitarian Order and the Deepening Entrenchment of the Ban on Girls’ Education

Four years into Taliban rule, the trajectory of governance reveals a clear trend: the consolidation of a totalitarian order driven by ideological purification, not social need, public demand, or national interest. The ban on girls’ education, initially framed as temporary, now stands as a key marker of this ideological consolidation. Instead of moderating, the Taliban have expanded and hardened their authoritarian governance, embedding their worldview into law, institutions, social norms, and daily life.

This section examines why hope for reversal has not only diminished but was always misplaced, and why the Taliban’s growing ideological coherence makes meaningful policy change increasingly improbable.

The Ideological Convergence of Power Consolidation and Gender Apartheid

Early analyses after 2021 often speculated that internal debate among “moderate” and “hardline” Taliban could eventually shift the group’s stance on girls’ education. However, it is now clear that the Taliban’s leadership—particularly the Supreme Leader and the clerical establishment in Kandahar—view gender restrictions not as negotiable policies but as proof of their ideological authenticity. Conceding on these restrictions would undermine the internal cohesion of the movement, the theological authority of the leadership, the patriarchal logic at the foundation of their political theology, and the symbolic distinction between their regime and the Republic.

Thus, the ban is not merely a policy choice; it is a badge of ideological purity.

The movement’s most powerful actors share a commitment to imposing a social order rooted in gender segregation, moral surveillance, and clerical control. The notion that schooling for girls beyond primary grades could fit within this order contradicts the core assumptions underpinning Taliban governance.

The Decline of Hope: A Four-Year Pattern of Escalation, Not Moderation

Any residual hope that internal pressures or diplomatic engagement might shift the Taliban’s position has faded. Over four years, the Taliban have:

– expanded restrictions on women’s mobility,– imposed new bans on women in public spaces and employment,– strengthened the authority of religious police,– criminalized debate or protest regarding girls’ education,– intensified censorship, and– increased moral regulation across all sectors.

These developments show a regime moving in one direction only: toward deeper institutionalization of patriarchal authoritarianism. The ban on girls’ education must be understood as part of this broader architecture, not an isolated issue. If anything, the regime’s ideological rigidity has grown more entrenched with time.

Hope did not “fade”; it was systematically dismantled.

Why the Taliban Reject Problem Recognition

One of the most critical obstacles to policy change is that the Taliban leadership refuses to recognize girls’ exclusion as a “problem.” Under Kingdon’s Streams Framework, no policy solution is possible unless decision-makers first acknowledge the existence of a policy problem.

But the Taliban leadership:

– does not perceive the ban as harmful,– does not accept the developmental or economic consequences,– does not recognize public demand as legitimate,– does not accept the idea of equal rights for women, and– does not interpret education as a universal right.

Instead, they frame girls’ education as a potential threat to moral order, ideological coherence, and religious purity. The Taliban leadership’s refusal to accept the problem framing makes any policy window dependent on political, not technical, shifts.

The Impact of External Shifts: Declining Pressure and Strategic Normalization

The decline in external pressure has further emboldened the Taliban. As global crises—particularly the Ukraine war and the Middle East conflict—shifted international attention, Afghanistan receded from the diplomatic agenda. Simultaneously, countries like Russia and China moved toward normalization of relations, giving the Taliban confidence that their ideological choices would not jeopardize international engagement.

This dynamic has strengthened the movement’s belief that ideological concessions are unnecessary for political survival.

International leverage has weakened not only because attention has shifted but because many states have signaled willingness to engage without conditions, reinforcing the Taliban’s ideological resistance.

The Internal Landscape: The Silencing of Civil Society and the Crushing of Advocacy

Inside Afghanistan, the Taliban have extinguished the actors who once created internal policy pressure:

– civil society groups have been dismantled,– women’s rights activists imprisoned or exiled,– tribal and community leaders silenced,– religious scholars intimidated, and– youth networks dismantled.

Without internal pressure, there is no domestic counterweight to Taliban ideology. The regime faces no organized resistance capable of shifting the internal political stream.

This absence of domestic counterpressure has made ideological decisions more stable—and durable.

The Closing of the Policy Window

The first 6–12 months of Taliban rule provided the strongest chance for change. Public mobilization, international unity, and regime instability aligned briefly, creating a potential opening. But that window has fully closed.

Why?

Internal repression weakened activist-driven pressure.

International distraction fragmented global consensus.

Regional actors avoided leveraging their influence.

The “moderate Taliban” narrative delayed decisive action.

The Taliban leadership solidified ideological control.

By 2023, the possibility of reopening girls’ schools had shifted from unlikely to implausible.

By 2024, it had become ideologically unacceptable within the Taliban’s inner circle.

The Expanding Totalitarian Order

The Taliban’s current governance displays the hallmarks of totalitarian systems:

– a unifying ideology,– absolute control over public and private behavior,– institutionalized surveillance,– elimination of pluralism,– gender apartheid as a structural practice, and– the weaponization of education.

This is not merely authoritarian rule. It is an attempt to engineer society.

Education is central to this project—not as a public good, but as an instrument of ideological reproduction.

Conclusion: No Policy Change Without Political Transformation

The Taliban will not alter their stance on girls’ education unless a political rupture, internal fracture, or shift in power reconfigures their strategic calculus. Technical solutions, humanitarian appeals, or religious persuasion will not suffice. The issue is ideological, not administrative.

Thus, any meaningful progress requires:

– external pressure tied to political costs,– internal realignments among Taliban elites, or– structural shifts in the regime’s stability.

Absent such changes, girls’ education will remain constrained by a political theology that rejects equality, autonomy, and modernity at their core.

The ban is not temporary. It is foundational to the Taliban’s vision of society.

Final Concluding Section: The Ideological Boundary of Girls’ Education and the Limits of Change under Taliban Rule

Four years after the fall of the Republic, the Taliban’s governance has become unmistakably clear. The exclusion of girls from education is not an anomaly, nor a temporary response to administrative challenges, nor a negotiable policy awaiting technical solutions. It is the ideological boundary that defines the Taliban’s political identity, legitimizes their authority, and distinguishes their regime from the modern Afghan state that existed from 2001 to 2021. Any hope for substantive reform must begin with this recognition.

A Missed Diplomatic Moment

In the early months after the Taliban takeover, a rare convergence of pressures emerged. Inside Afghanistan, residents voiced strong and diverse support for girls’ education; outside, the world’s attention was sharply focused on the unfolding crisis. This alignment briefly created the conditions described in Kingdon’s policy framework—where the problem, policy, and political streams intersect to create a window for reform.

However, this window closed quickly. Countries with diplomatic leverage—Pakistan, Qatar, China, the UAE—failed to use it. Each had both the access and political capital to influence the Taliban, but each made a strategic choice to prioritize its own interests over Afghan women’s rights. Their caution, ambiguity, or silence allowed the Taliban to delay, deflect, and ultimately consolidate their stance.

Meanwhile, Western actors fell into a familiar trap: believing that “moderate Taliban” figures could be empowered to counterbalance the hardliners. In reality, these moderates performed the same role they had during the Doha negotiations—managing optics, not policy. Their assurances that the ban was temporary convinced many actors to wait and hope rather than apply decisive pressure.

By the time the global spotlight shifted to Ukraine and other geopolitical crises, the moment had passed; the Taliban recognized it and acted swiftly. The policy window shut, and the regime moved to institutionalize its ban.

Ideology, Not Logistics

The Taliban’s unwillingness to reverse the ban is best understood through their ideological framework, not through the shifting excuses they deploy. Over the past four years, they have offered multiple justifications:

– cultural norms– modesty and moral protection– logistical constraints– safety concerns– the need for “Islamic” educational environments

But these rationales are strategically malleable. As soon as one is questioned, another emerges. Zabihullah Mujahid’s August 14 interview is illustrative: he reframed the ban not as exclusion, but as “kindness,” insisting that girls must be protected and that the Supreme Leader is motivated only by safeguarding their chastity (ʿiffat). This paternalistic rhetoric is not meant to persuade; it is meant to obscure the deeper ideological truth.

The Taliban’s worldview constructs gender hierarchy as divinely mandated, the public sphere as the domain of men, and education as a pathway that must be tightly controlled to prevent moral contamination. Within this framework, granting girls broad educational access is not simply difficult—it is heretical.

Thus, the problem is not logistical; it is doctrinal. And doctrinal problems cannot be solved with technical solutions.

The Political Stream: Why Change Is Unlikely

Under Kingdon’s model, a policy window reopens only when the political stream shifts: changes in leadership, elite alignment, public mobilization, or external pressure alter the incentive structure of decision-makers. None of these conditions exist today.

– Internally, civil society has been dismantled.– The public sphere is silenced through coercion.– Religious scholars who support girls’ education face intimidation.– The Taliban’s base largely consumes ideology through madrassas and internal propaganda.– Externally, countries like Russia, China, and Iran are moving toward normalization, signaling that the Taliban can entrench their ideology without jeopardizing international legitimacy.

Without political costs, ideologically motivated policies remain protected. And within the Taliban’s doctrinal universe, girls’ education beyond the primary level is precisely such a protected domain.

No Change Without Ideological Rupture

The uncomfortable truth—and the one that must be acknowledged openly—is that the Taliban cannot provide equal education for girls without abandoning their core ideological commitments. Every component of their worldview would have to shift:

– their theological interpretation of gender,– their political theology of obedience and moral policing,– their suspicion of modernity,– their belief that women’s presence in public is destabilizing,– and their fear that education empowers dissent.

These are not peripheral ideas; they are the pillars of the Taliban’s identity. As long as this ideological foundation remains intact, any form of girls’ education will be limited, instrumentalized, or designed to reproduce Taliban doctrine.

There is no “technical solution” to an ideological problem. There is only ideological transformation—or regime change.

The Necessary Honesty for Future Policy

The global community, Afghan civil society in exile, and researchers must therefore adopt a more realistic framework. No meaningful change will occur unless:

Internal political dynamics shift, creating fractures or incentive changes within the Taliban elite;

External pressure becomes strategically coordinated and tied to real political or economic consequences;

The Taliban’s ideological legitimacy is challenged, rather than accepted as an immutable reality; or

A new political configuration emerges that is not governed by the Taliban’s totalitarian theology.

Without one of these conditions, the ban on girls’ education will remain not only in place but foundational to the Taliban’s governing identity.