Intellectual Silence against Taliban's Religious Extremism in Afghanistan

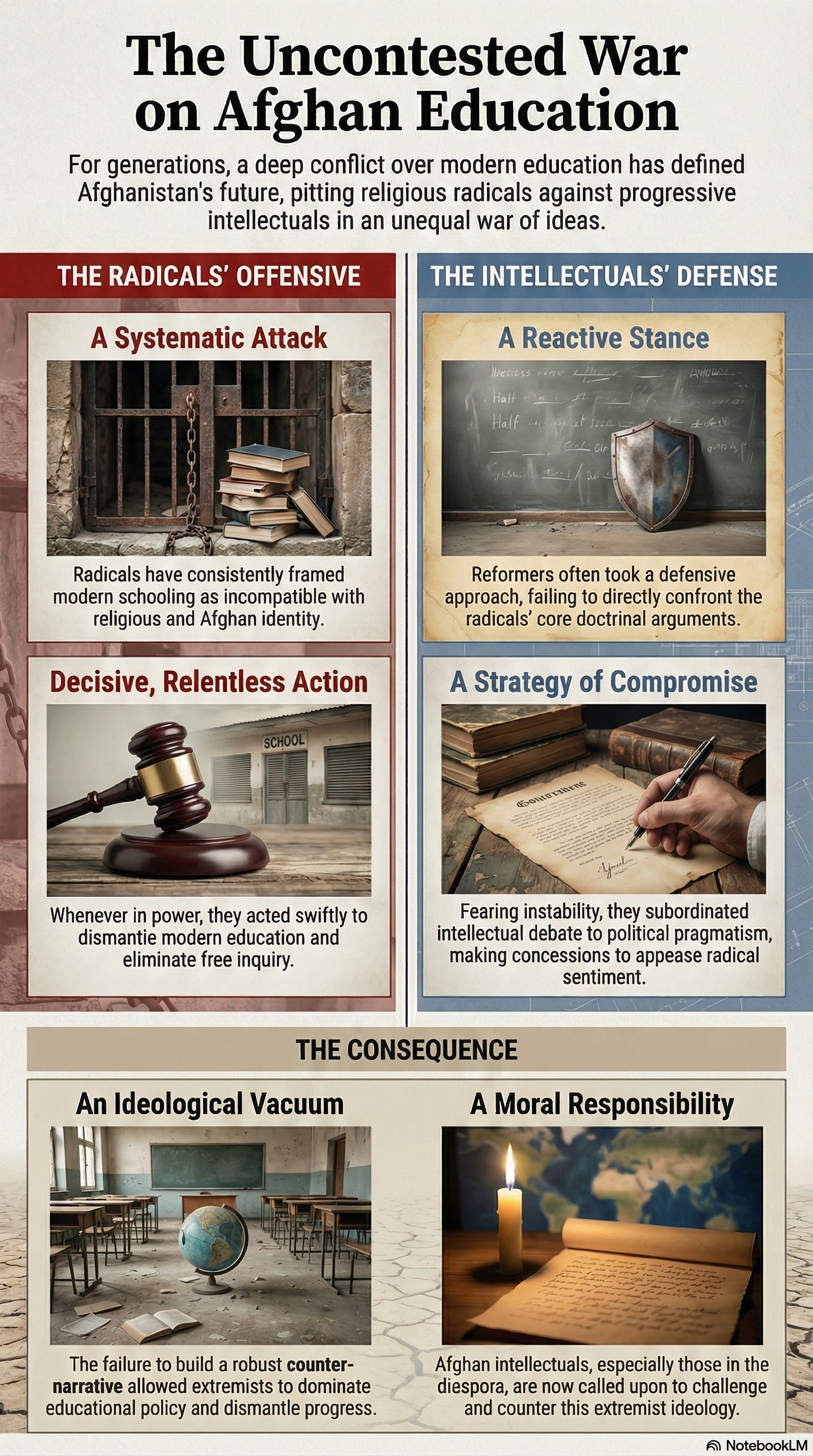

There has historically been no common ground between religious extremists and Afghan intellectuals, and ultimately, the intellectuals were unable to counter effectively the extremists arguments.

Afghan intellectuals and secular thinkers—defined here as individuals who value scientific inquiry, human experience, rational reasoning, and critical thought, regardless of their level of education or place of residence—have historically encountered significant challenges in presenting coherent, evidence-based arguments and in maintaining effective public critiques against religious radicalism. This shortcoming is particularly noticeable in discussions about modern education, human rights, and democratic values. It is striking, especially considering the intellectual resources, institutional access, and support many in this group have had. Instead of leveraging these advantages to form a united intellectual front, they have struggled to effectively challenge an ideological movement that poses a threat to their intellectual and professional existence. Rather than developing a collective counter-vision, many have opted to accommodate the status quo, seeking security through alignment with ruling authorities for employment and protection, or have become mired in internal divisions based on ethnic, religious, and linguistic differences.

In contrast, religious radicals have consistently articulated a clear and adaptable ideological stance since the rise of the reformist movement, the first Afghan intellectual movement, in the early twentieth century. They effectively adjusted their discourse and strategies to changing social and political landscapes, allowing them to sustain momentum. Whether operating within the state apparatus during the Republic era or mobilizing against it during the Taliban insurgency, they seized every opportunity to expand their influence and promote their worldview. A key aspect of their agenda has been a continuous challenge to intellectual, egalitarian, and reformist ideas, particularly evident in their systematic opposition to public and modern education.

Religious radicals have systematically framed modern schooling as fundamentally incompatible with religious views, creating an ideological divide that positions their interpretation of religious learning as superior and more authentically “Afghan.” This narrative has fostered a long-standing tension—indeed, a deep-seated antagonism—between religious and modern educational models. Attempts to integrate religious teachings within modern frameworks have often faced radical backlash, reversing hard-won reforms, as seen in the prohibition of modern schools in 1929, the Taliban’s assault on education in the mid-1990s, and the current ban on girls’ schooling.

The historical evidence highlights a clear contest between two opposing worldviews. Religious radicals like the Taliban have remained steadfast in their anti-modern stance, persistently seeking to influence educational policy according to their doctrinal priorities. The Taliban era exemplifies this position: the movement has consistently expressed hostility towards modern schooling and resistance to free inquiry.

In contrast, Afghan progressive thinkers—both historically and during the Republic (2002–2021)—have often taken a defensive and reactive approach. Reformists advocated for the necessity of modern schooling but rarely engaged with the radicals’ claims within their religious, cultural, or intellectual contexts. Throughout the twentieth century, intellectuals operated under political volatility, maintaining rhetorical support for modern education while shying away from confronting the doctrinal arguments posed by radical actors, fearing that such confrontations could destabilize the political or social order.

This tendency persisted during the Republic, where policymakers and intellectuals often deflected responsibility for countering the Taliban’s extremist rhetoric or exposing its logical inconsistencies—particularly regarding women’s and girls’ education—by attributing resistance to “culture” or making concessions on schools and curricula to appease radical sentiments. Consequently, they failed to present a coherent intellectual response capable of challenging the foundations of extremist ideology.

The implications of this failure were profound. During the Republic, the reluctance to directly challenge radical narratives fostered a persistent vulnerability, as policymakers feared provoking backlash. Under the Taliban, this vulnerability has resulted in explicit, policy-driven attacks on modern education. The lack of a robust intellectual counter-narrative has allowed radicals to continue their assault on modern institutions without facing significant resistance. Thus, whenever the Taliban regained power, they acted decisively—dismantling modern learning structures and eliminating spaces for free intellectual inquiry.

While the current educational crisis can primarily be attributed to religious radicals, Afghan intellectuals must also recognize their own shortcomings. They had the historical opportunity, institutional space, and scholarly resources to critically examine and counter radical interpretations—whether related to seminaries, curricula, or the relationship between religious education and Afghanistan’s rich intellectual tradition. Yet scholarship became intertwined with political considerations, driven by the need for stability, compromise, and power. When intellectual inquiry is subordinated to political pragmatism, it inevitably reaches an impasse. In Afghanistan, this impasse left the field of educational ideology largely uncontested—allowing radical actors to define the narrative, shape policy, and ultimately determine the future of modern education.

All Afghan intellectuals—especially those in the diaspora who possess the safety and freedom to speak—now bear a moral responsibility to critique, challenge, and counter the Taliban’s radical ideology, as well as that of other extremist groups, and to contribute to freeing the nation from this form of ideological occupation.