An Insider Enemy: The Bureaucracy as Barrier for Education Equity in Afghanistan

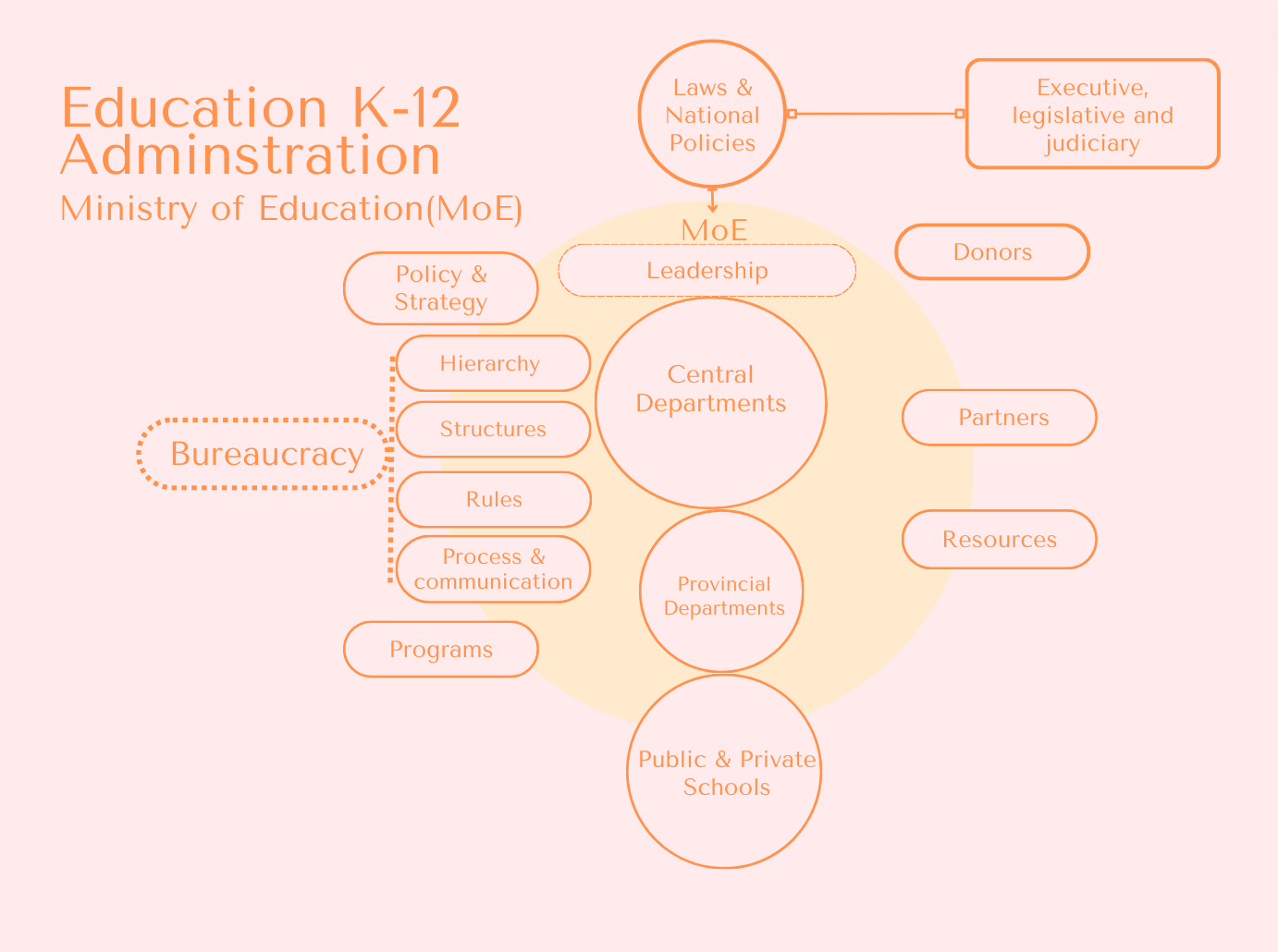

The education system in Afghanistan faces significant challenges, both political and bureaucratic. The former relates to the Taliban regime's discriminative policy on education that excludes girls from equitable access to education (Human Rights Watch, 2022). The latter, the interest of the current article, pertains to inefficiencies in the system that existed before and are exacerbated by the Taliban's rule - incapacitating the education system from within.

1. The Brief Historic Prospect

The formation of the Ministry of Education (MoE) bureaucracy, defined as a distinct administrative body for governing the nation's education, occurred in the early 20th century (Naumann, 2011). In the mid-20th century, the MoE's bureaucracy grew, evolved, and expanded. This development aimed to establish a cadre of bureaucrats known for professionalism, efficiency, and strict discipline. In support of this, international organizations and newly trained experts assisted the MoE with achieving these aims (Samady, 2001; Spink, 2005; Majrooh, 1987).

Nevertheless, in the late 20th century, due to the Soviet invasion and the ensuing civil war, the bureaucracy became an instrument for ruling ideologies (Elmi, 1987). This shift led to rulers adding extra bureaucratic layers, rules, and processes (Samady, 2001; Elmi, 1987). Consequently, the changes exerted control, directed education, and propagated the ruling ideologies (Elmi, 1987).

2. Overview of Bureaucracy in the Republic Era

As the century turned, with the beginning of the 21st century, two decades-long bureaucratic reforms (2002 - 2022) started. Concurrent with this, the 2004 democratic constitution mandated the MoE grant equal education access. This provision, coupled with bureaucratic reforms, led to excessive bureaucracy. To address this, in 2017, the National Education Strategic Plan (NESP)-III emphasized efficient and transparent bureaucracy. The Plan prioritized structure reforms to shift the MoE's bureau towards a more outcome-oriented approach (IIEP-UNESCO, 2018). It led to initiatives that reformed the rules, procedures, structures, and hierarchies (MoE, 2020).

The reforms produced several positive outputs. They shortened several procedures, regulated some departments, and improved the communication pathways within and between them (MoE, 2020). Most importantly, the bureaucracy became receptive to female teachers and employees (Ahmadi, 2023). It developed a culture where women could work (Jones, 2008).

However, these achievements couldn't preclude setbacks and challenges. The MoE bureaucracy had a weak accountability and transparency system. As evidenced, it lacked an "adequate payroll system" and "basic auditing practices" (Khan, 2015). This led to systemic corruption at the MoE and the loss of many opportunities. A study revealed that out of 15,152 schools, 1,174 were "ghost schools," equating to one in every twelve. Annually, around $12 million is allocated to pay the ghost teachers' salaries, according to estimates (Khan, 2015). This kind of corruption disproportionately affects society's most vulnerable and marginalized groups (International Transparency, 2013). It caused around "3.7 million children - 60% girls-" to remain out of school (UNICEF, n.d.).

On a theoretical level, David Graeber (2016) posits that bureaucratic processes can create "dead zones" of imagination and stifle the potential for innovation and creativity. Illustrating this, the MoE's bureaucracy increased the number of students in public schools, but it failed to enhance the quality (Niaz et al., 2019; Arooje & Burridge, 2021). Hence, the discourse on education quality was often overlooked. Thus, the bureaucracy was mainly concerned with implementing activities rather than the results and outcomes (Lan, 2022).

3. The Taliban Era

The fall of the Republic further increased the bureaucratic challenges fueled by the Taliban's discrimination policies. Less than a month after taking power, the Taliban ordered women to stay indoors. They banned co-education, girls' secondary schools, and female employees from offices (Ahmadi, 2022). These decisions affected over 1 million female students and tens of thousands of female teachers and employees(Butt, 2023).

This policy shift devastated impacts on bureaucracy. From a broader perspective, Peters (2018) posits that bureaucracy has become more critical for implementing public policy. Pivoting to the specific case, the Taliban implemented wider changes to turn bureaucracy into an instrument of their policy. They appointed their members in all leadership and managerial positions and tasked them to Indoctrinate the lower-ranking employees. The Talib bureaucrats gave the employees two options: obey or quit. Most, of course, selected the primary option to survive. In conjunction with this, the MoE partnered with the intelligence directorate and the Ministry of Vice and Virtue to track the employees and purify their beliefs. The justification for such measures is rooted in their leaders’ belief that during the Republic era, people were brainwashed with Western propaganda — they must purify them (MoE, 2022).

Building upon this, they shut down some departments focusing on quality education. These include the teacher training centers and the monitoring and evaluation department (Ellingwood, 2023; Jozniak, 2023). To further consolidate their control, they revised and changed the bureaucratic rules to strengthen their iron cage in schools. As an illustration, only in 2022 did they plan to modify more than 50 policies, guidelines, and regulations (Ministry of Education, 2022). Continuing this trend, they began syllabus and curriculum changes and finished revising the primary grades' textbooks (Ministry of Education, 2023).

The multitude of bureaucratic changes (Ministry of Education, 2022) solidifies their control over schools. It will ease the dissemination of their ideology —previously limited to approximately 80,000 militants —to the nation's vast young population. With time, these practices will likely be normalized and woven into the country's cultural tapestry.

References

1. Ahmadi, B. (2022, December 8). The Taliban Continue to Tighten Their Grip on Afghan Women and Girls. United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/12/taliban-continue-tighten-their-grip-afghan-women-and-girls

2. Ahmadi, B. (2023, April 13). Taking a Terrible Toll: The Taliban's Education Ban. United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/04/taking-terrible-toll-talibans-education-ban

3. Arooje, R., & Burridge, N. (2021). School education in Afghanistan: Overcoming the challenges of a fragile state. In Handbook of education systems in South Asia (pp. 411-441). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

4. Butt, R. (2023, September 17). 2 years ago, the Taliban banned girls from school. It's a worsening crisis for all Afghans. AP News. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://apnews.com/article/afghanistan-taliban-high-school-ban-girls-7046b3dbb76ca76d40343db6ba547556

5. Ellingwood, A. (2023, July 15). The Taliban shut down teacher training centers, leaving thousands out of jobs. The majority of the students were women. Feminist Majority Foundation. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://feminist.org/news/the-taliban-shut-down-teacher-training-centers-leaving-thousands-out-of-jobs-the-majority-of-the-student-were-women/

6. Human Rights Watch. (2022, March 20). Four Ways to Support Girls' Access to Education in Afghanistan. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/20/four-ways-support-girls-access-education-afghanistan

7. IIEP-UNESCO. (2018, February 12). 3 pillars of Afghanistan's education plan | IIEP-UNESCO. iiep-unesco. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://www.iiep.unesco.org/en/3-pillars-afghanistans-education-plan-4379

8. International, T. (2013). Global Corruption Report: Education. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

9. Ionescu, Luminiţa, George Lăzăroiu, and Gheorghe Iosif. "Corruption and bureaucracy in public services." Amfiteatru Economic Journal 14, no. Special No. 6 (2012): 665-679.

10. Jones, A. M. (2008). Afghanistan on the educational road to access and equity. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 28(3), 277-290.

11. Jozwiak, R. (2023). Taliban Closes Education Ministry Department, Creating Uncertainty For Thousands. RFE/RL. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-education-layoffs-fears/32749748.html

12. Khan, A. (2015, July 9). Ghost Students, Ghost Teachers, Ghost Schools. BuzzFeed News. Retrieved February 18, 2024, from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/azmatkhan/the-big-lie-that-helped-justify-americas-war-in-afghanistan

13. Lan, J. (2022). A Review of Afghanistan's National Education Strategic Plan (2017-2021). Pacific International Journal, 5(3), 10-17.

14. Majrooh, S. B. (1987). Education in Afghanistan: Past and present—A problem for the future. Central Asian Survey, 6(3), 103-116.

15. Ministry of Education. (2022). National Action Plan -2022. Ministry of Education.

16. MoE, (2020). Annual reports. The Ministry of Education Publication.

17. MoE, (2022). Annual reports and press briefs. The Ministry of Education Publication.

18. MoE, (2023). Annual reports. The Ministry of Education Publication.

19. Naumann, C. (2011). Modernizing Education in Afghanistan. Cycles of Expansion and Contraction in Historical Perspective. Lisbon: Periploi.

20. Niaz Asadullah, M., Alim, Md. A., & Anowar Hossain, M. (2019). Enrolling girls without learning: Evidence from public schools in Afghanistan. Development Policy Review, 37(4), 486–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12354

21. Peters, B. G. (2018). The politics of bureaucracy: An introduction to comparative public administration. Routledge.

22. Samady, S. R. (2001). Education and Afghan Society in the Twentieth Century. France: UNESCO.

23. Samady, S. R. (2013). Changing profile of education in Afghanistan.

24. Spink*, J. (2005). Education and politics in Afghanistan: the importance of an education system in peacebuilding and reconstruction. Journal of Peace Education, 2(2), 195-207.

25. UNICEF. (n.d.). Education. UNICEF. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://www.unicef.org/afghanistan/education.