Afghanistan’s Intellectual Rise and Decline (9th–17th Century)

The region now called Afghanistan has a long and complex history, marked by alternating periods of intellectual flourishing and devastating decline. Positioned at the crossroads of Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and the Iranian plateau, Afghanistan historically served as a major corridor for trade, cultural exchange, and scholarly interaction. However, this strategic location also rendered it highly vulnerable to successive waves of conquest and external domination, with long-lasting consequences for its intellectual and institutional development.

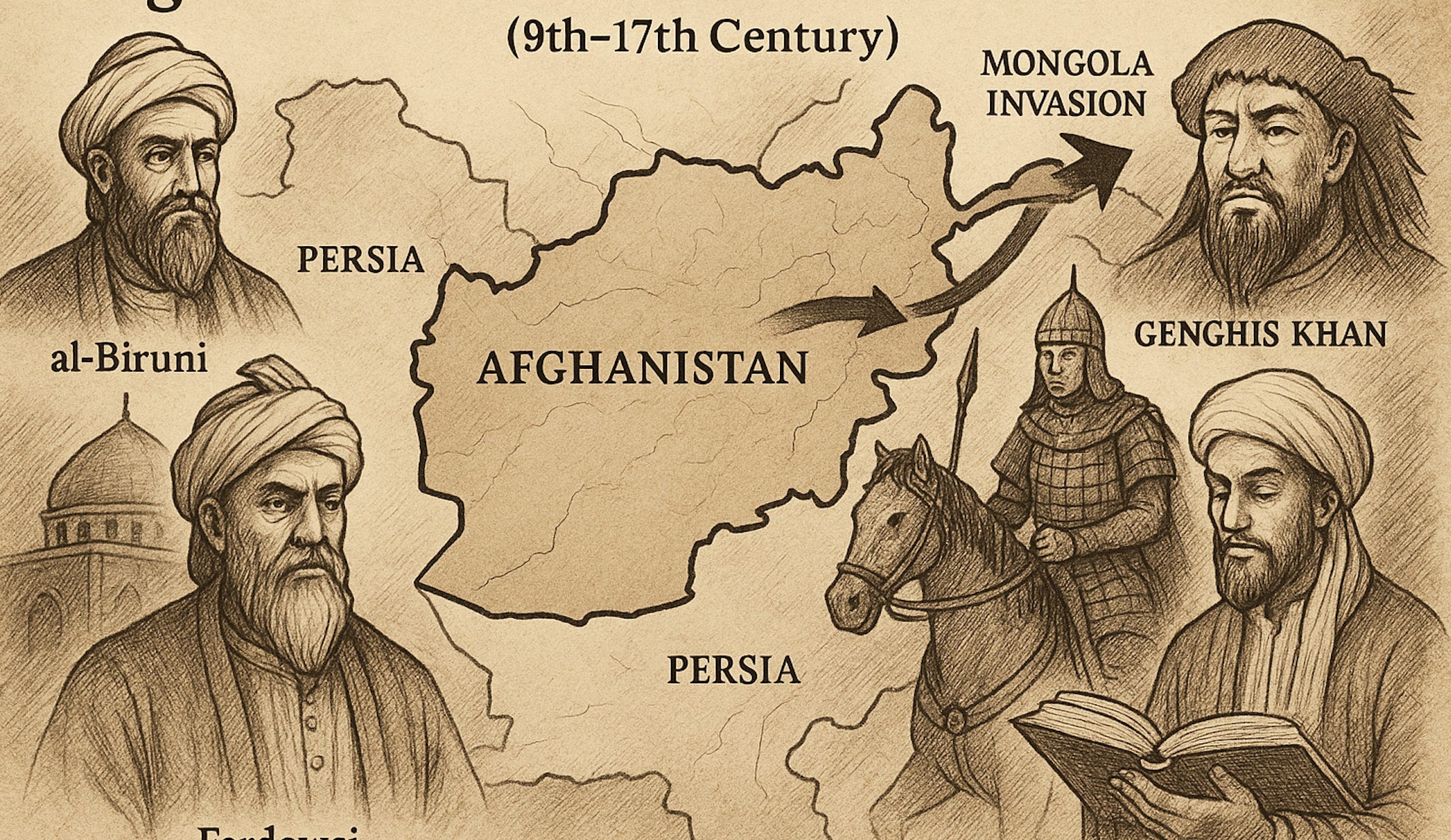

Following the Arab conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries, Islam gradually displaced the Greco-Buddhist cultural legacy that had flourished under the Kushans, particularly in cities such as Balkh, which had been one of the most important intellectual centers in the region. By the 9th and 10th centuries, under the Tahirid, Saffarid, and Samanid dynasties, Afghanistan became part of a broader central Asian cultural renaissance. Cities such as Balkh and Herat emerged as vibrant centers of learning, scientific inquiry, literature, and philosophy. This intellectual golden age reached its peak in the 11th and 12th centuries when patrons supported scholars, poets, and philosophers, including al-Biruni and Ferdowsi.

This trajectory was violently disrupted in the early 13th century. In 1220, the Mongol invasion led by Genghis Khan devastated much of what is now northern and central Afghanistan. Major urban centers such as Balkh, Herat, Ghazni, and Bamiyan were razed to the ground. Populations were massacred, libraries and irrigation systems destroyed, and agricultural lands rendered barren. The scale of destruction was so immense that, even after more than two centuries, the region failed to regain its former levels of urban vitality, demographic strength, or scholarly prominence.

The long-term consequences were profound. Urban depopulation, the disintegration of trade routes, and the collapse of scholarly institutions left Afghanistan a shadow of its pre-invasion self. Although a cultural revival occurred in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, especially under the Timurids in Herat, it was largely confined to elite circles and urban courts. The Timurid capital of Herat briefly regained its status as a hub of artistic and literary production, attracting figures such as Jami and Bihzad. However, this renaissance was geographically limited and lacked the structural foundations necessary to sustain widespread intellectual renewal. As S. Frederick Starr notes in The Genius of Their Age, the transformation of knowledge into institutional and scientific advancement requires autonomy, tolerance, and patronage—conditions that were increasingly absent in the Afghan context.

By the mid-15th century, the brief Timurid revival gave way to a prolonged era of stagnation. The suppression of rationalist traditions, rising religious orthodoxy, and increased state control over education narrowed the intellectual landscape. Institutions that had once hosted vibrant debates on philosophy, medicine, and the natural sciences were transformed into madrassas focused primarily on religious orthodoxy and memorization. The pursuit of knowledge became subordinate to political loyalty and theological conformity.

The 16th century marked a new period of geopolitical fragmentation. Three competing empires—the Safavids of Persia (1501–1736), the Uzbek Shaybanids in Central Asia, and the newly founded Mughal Empire in India (established in 1526 by Babur)—fought for control over Afghanistan. Herat, Kandahar, and Kabul changed hands multiple times as Afghanistan became a contested frontier. Religious sectarianism intensified during this period, with the Safavids enforcing Shi‘ism in the west and the Sunni Uzbeks asserting a more rigid orthodoxy in the north. Afghan society was caught between these rival imperialisms, with little space for independent governance or cultural renewal.

During the region’s intellectual high points, scholars had often been funded by independent patrons—especially merchants, local notables, and civic endowments—which provided space for relatively autonomous inquiry. But as political centralization and sectarianism increased, this support system eroded. Scholars became increasingly reliant on rulers for funding, and patronage came with conditions. Knowledge was expected to legitimize power, not challenge it. This led to the institutionalization of orthodoxy, the marginalization of philosophical inquiry, and the erosion of scholarly autonomy. Madrassas increasingly reinforced state ideology rather than cultivating independent thought.

By the mid-16th century, Afghanistan entered what may be termed a "frozen era"—a prolonged period of cultural and economic stagnation. Global transformations, such as the rise of European maritime empires and the redirection of global trade through sea routes, bypassed Afghanistan and Central Asia entirely. The Silk Road gradually declined, and cities such as Kabul, Herat, and Kandahar lost their commercial significance. With declining trade, Afghanistan’s urban economy contracted, and a feudal socio-political order reasserted itself. Tribal chieftains and landed elites became the dominant power brokers, often at the expense of urban merchant and scholarly classes.

This decline affected every sector of society. The merchant class, once a critical patron of intellectual life, was reduced in influence. Learning institutions became conformist and insular, with little tolerance for innovation or dissent. Scientific and philosophical production virtually ceased. The agricultural economy, already weakened by the destruction of its irrigation systems during the Mongol and Timurid invasions, became increasingly dependent on neglected and inefficient systems like qanats and kariz. Most of the country reverted to subsistence-level farming. Whatever modest gains had been achieved in the 10th and 11th centuries were effectively undone.

By the 17th century, Afghanistan had been transformed from a thriving intellectual and commercial center into a politically fragmented, rural, and feudal society. Its scholarly traditions had been reduced to narrowly defined religious orthodoxy, and its economic and political institutions were structurally weakened by centuries of war, sectarianism, and isolation. The cumulative effect of these events left Afghanistan intellectually isolated and institutionally fragile on the eve of the modern era.

Note: This article is still a work in progress, and you can expect changes as I add more descriptions and analytics.

References:

Starr, S. Frederick. The Genius of Their Age: Islamic Science in the Golden Age of Central Asia.

Azad, Arezou. "The Beginnings of Islam in Afghanistan." University of California Press.

Gregorian, V. (1969). The emergence of modern Afghanistan: Politics of reform and modernization, 1880–1946. Stanford University Press.