"Afghanistan Education Situation Report 2025" Misses the Point: This Is Not a Problem—It Is Educational Repression

The Afghanistan Education Situation Report 2025, jointly published by UNICEF and UNESCO, aims to provide an overview of education under Taliban rule, addressing access, quality, and system performance across primary, secondary, and higher education.

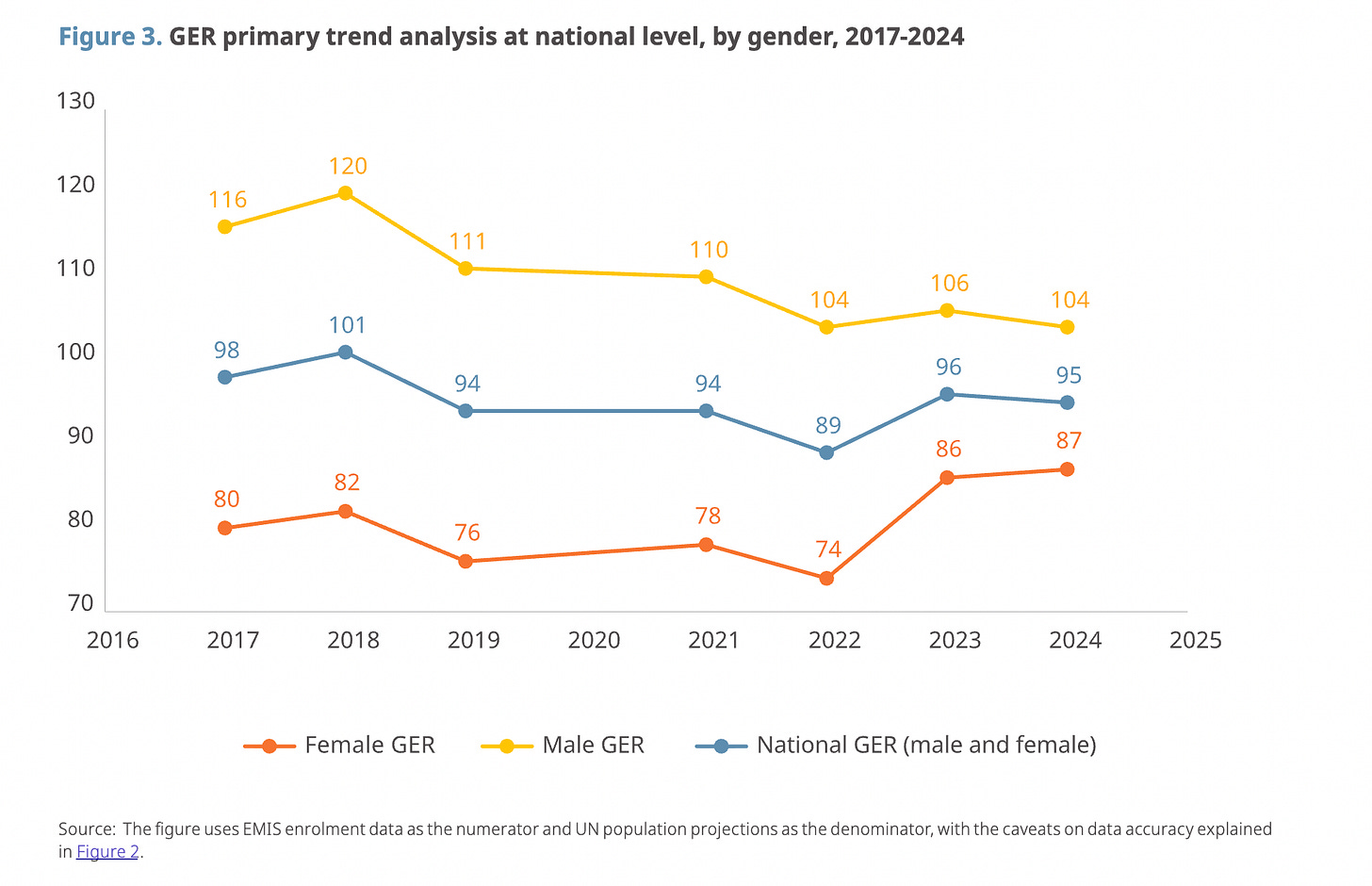

The main concerns regarding the Report pertain to its scope and methodology. Substantively, the Report focuses primarily on identifying problems but lacks essential explanatory discussion. This is particularly significant when using the Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) to assess the public schooling system’s ability to integrate out-of-school children into formal education. By not addressing the structural and contextual factors influencing GER trends—such as age-grade distortion, repetition rates, administrative practices, and demographic uncertainties—the analysis leans more towards description rather than a thorough analysis.

Methodologically, the weaknesses are even more evident. The Report relies predominantly on data from the Education Management Information System (EMIS), the Ministry of Education’s administrative database. EMIS has long struggled with issues of data accuracy, consistency, and verification. Under the Taliban’s de facto rule, independent access to and validation of EMIS data is nearly impossible, heightening the risk of systematic distortion, political manipulation, or administrative inflation. In this context, depending on a single administrative source without a transparent validation process raises significant concerns about credibility.

Additionally, the Report does not provide a clear strategy for data verification or validation. There is no evidence that triangulation with independent sources—such as household surveys, international datasets, or third-party assessments—was conducted to validate enrollment figures. The Report also fails to specify which indicators should be interpreted with caution due to known limitations in the numerator or denominator estimates. This lack of methodological safeguards prevents readers from assessing the reliability of the reported trends. As a result, the credibility of the enrollment figures—especially those related to secondary education and gender disaggregation—remains challenging to evaluate.

The following section will highlight key components of the Report for a detailed critical analysis, concentrating on both substantive interpretation and methodological integrity.

A Key Issue in the Report’s Evaluation of the Public Schooling System’s Capacity via GER

Note: Table extracted from the Report explaining GER at Primary Level for Boys and Girls.

In this Report, the GER is a crucial metric for assessing the participation and capacity of Afghanistan’s education system. It is widely used by UN agencies and education researchers, making it a suitable proxy indicator in situations where reliable age-specific enrollment data is unavailable. The EMIS faces numerous shortcomings, particularly under the current regime, and does not provide students’ ages, which is essential for calculating the Net Enrollment Ratio. In such contexts, GER stands out as the relevant and appropriate measure for cross-provincial and longitudinal analysis.

However, this choice comes with significant caveats, particularly concerning the denominator. Afghanistan’s last national census was conducted in 1979, and since then, all population estimates from the National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA) or international organizations are based on projections using assumed annual growth rates. These projections do not completely capture the effects of four decades of conflict, internal displacement, refugee movements, changing fertility rates, and uneven demographic shifts across provinces. Consequently, both the NSIA and the UN are producing different population figures, and estimates of the school-age population—the basis for GER calculations—are inherently uncertain. This uncertainty limits the interpretation of GER trends, especially at the provincial level where migration and displacement have been inconsistent.

There is some ambiguity surrounding the definition of “official school age.” While the Education Law indicates that the age range for entering first grade is between six and nine, the Report does not clarify whether the official entry age used is strictly seven years or aligns with the age range specified in the Law. This is a crucial issue, as it impacts approximately 30 points of the GERs, potentially lowering them if the age definition from the Education Law is applied. This inconsistency complicates the accuracy of the denominator in the Report’s data presentation.

On the numerator side, further methodological issues arise. The Ministry of Education has been known to keep students on enrollment lists for extended periods—sometimes up to three years—after they have effectively left school. This practice inflates enrollment figures and obscures actual dropout rates, particularly at the secondary level. Official EMIS data report over two million secondary students, including girls, despite documented restrictions on girls’ education beyond Grade 6 under the current regime. Thus, enrollment figures for girls in Grades 7–12 often exist in administrative records but do not reflect actual classroom attendance. Additionally, the Report does not clarify whether the total enrollment figures pertain solely to public schools or if they also include private institutions and non-formal education, such as community-based programs.

It is crucial to acknowledge these constraints on both the numerator and denominator. GER should not be viewed as a precise measure of age-appropriate access or actual attendance; rather, it reflects the reported enrollment capacity relative to projected population cohorts, capturing participation levels under imperfect demographic and administrative conditions.

The failure of the Report to clearly address these methodological limitations undermines its analytical credibility. In a politically sensitive environment where independent verification of EMIS data is severely limited, the lack of a well-defined validation strategy—such as triangulation with household surveys or independent evaluations—raises valid concerns about data reliability. A thorough analysis must therefore highlight these caveats, enabling readers to interpret observed trends with appropriate caution.

What are the reasons for the GER exceeding 100?

Another important issue that requires careful consideration is the interpretation of GER values above 100. While the Report views GER levels over 100 as a clear sign of increasing system capacity, this interpretation is somewhat simplistic. A more nuanced analysis shows that GER values above 100 come with various methodological and structural caveats.

First, GER exceeds 100 when students outside the official age range—both over-age and under-age—are enrolled in school. In contexts where delayed entry is common or grade repetition is prevalent, a significant number of over-age students can inflate total enrollment relative to the official school-age population. This does not necessarily indicate improved access or efficiency; rather, it may highlight age-grade distortion within the system. When GER rises significantly beyond 100—especially toward 150 or higher—it may indicate systemic inefficiencies such as delayed progression, high repetition rates, or administrative retention of students on enrollment lists.

Second, the dynamics of repetition and dropout further complicate the interpretation of GER. In systems where students repeat grades or where administrative records do not promptly remove dropouts, enrollment totals can remain artificially high. This situation creates a form of “silent exclusion,” where students are counted within the system statistically, even if they are not making meaningful progress or attending school. Such practices inflate the numerator of the GER while obscuring underlying issues in grade progression and completion.

Third, extremely high GER values may reflect overcrowding or strain on infrastructure rather than healthy growth. When total enrollment significantly exceeds the official-age population, the system may be absorbing students inefficiently, potentially compromising quality and instructional effectiveness. This is particularly relevant in public schooling systems, such as Afghanistan’s, where planning is influenced by both demand and supply, and demand analysis is based on the school-age population in the denominator.

These interpretive factors are crucial for scholars and professionals who use GER as an indicator of system performance. Without a transparent discussion of age-grade distortion, repetition, dropout recording practices, and uncertainties in the population denominator, GER trends can be misinterpreted as unqualified success. A thorough analysis must, therefore, go beyond descriptive reporting and critically examine the structural conditions that lead to GER values above 100. Only through such scrutiny can GER be a meaningful indicator rather than merely a superficial marker of expansion.

Identifying the Problem Without Addressing the Causes

The Report focuses solely on the problems at hand, without addressing the underlying causes or political factors that influence these issues. Although it includes the term “Situation” in the title, indicating a broader inquiry beyond the numerical data, it does not delve into the contextual meanings associated with the situation. One significant omission is the institutional aspect, specifically the changes in the national policy framework for education. For instance, the Report fails to examine how the notorious and discriminatory Law on the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice shapes and restricts education policy. It also overlooks how the policy-making process itself has changed. Decision-making that was once centralized in the MoE has now shifted, yet the Report lacks an analysis of how this restructuring affects educational governance. These changes in authority and scope are essential, especially if the Report aims to contribute to discussions on educational reform in Afghanistan. If the MoE is no longer the primary decision-making body for key education policies, fundamental questions arise: Who are the current decision-makers? How are policies now developed and enforced?

An important aspect missing from the Report is the role of school-based management and social accountability in the schooling system, which is essential in the current suppressive environment. Community involvement remains one of the few mechanisms that can protect schools from abuse, political interference, and arbitrary changes imposed by the regime. This raises the question of the role of civil society, local councils, and school councils in education governance. The de facto authorities have long prohibited school councils and community shuras, effectively excluding communities from school affairs. This move aims to transform schools into traditional authoritarian madrasa-style institutions, devoid of public participation, transparency, and accountability to parents. This represents a significant structural issue that directly impacts school governance and educational outcomes. The Report should have highlighted this gap and underscored the urgent need to restore and strengthen participatory school governance, drawing on successful experiences from the Republic era where community-based participation enhanced access, school safety, and accountability.

The recommendations section is a crucial yet absent component of the Report. While it thoroughly discusses the issues, it does not address the vital question: what are the solutions?

Although proposing solutions might seem outside the scope of a technical document, given the current educational crisis in Afghanistan, a forward-looking section is as important as problem analysis. Without a clear roadmap, the Report risks becoming just another descriptive document lacking actionable direction. UNICEF, UNESCO, and other UN agencies are expected to play a key role in shaping the educational aspect of the UN’s MOSAIC framework for Afghanistan, which remains one of the most significant international roadmaps for engagement in the country, despite its limitations. Therefore, the Report should include a clear set of policy recommendations and a separate annex on education that outlines not only the problems but also their causes and practical solutions, providing a credible path forward for both national stakeholders and international partners.

Despite these limitations, one section of the Report is particularly noteworthy for its clarity: it accurately identifies the Taliban’s education policies as a direct cause of systemic collapse. Unlike prior reports that attributed failures to conflict or economic crisis, this one recognizes the deliberate policy decisions driving educational decline. The Taliban have shifted the education system toward ideological indoctrination rather than genuine learning, significantly expanding madrasa-style religious instruction. They have implemented a unified curriculum for Grades 1–6 that allocates nearly half of teaching time to Islamic subjects, displacing essential subjects like mathematics, science, and social studies. Official communications to schools mandate reduced instruction in languages and social sciences in favor of religious education and selective STEM subjects aligned with the regime’s ideological agenda. This is not education reform; it is educational re-engineering.

The Report reinforces that girls are disproportionately affected by Taliban policies, with 2.2 million adolescent girls excluded from education, and an additional 397,000 losing access each year.

The Report uses the World Bank’s report, Afghanistan Learning Poverty Report, published last year, and reinforce that learning is not happening in Afghan schools – according to the Report, 93 percent of children completing primary school in Afghanistan cannot read a simple text, ranking it among the worst-performing education systems globally.

The Report notes that nearly half of schools lack basic water and sanitation, over 1,000 schools remain closed, and child labor and child marriage are on the rise due to educational exclusion. Over 90 percent of the Ministry of Education budget is allocated to salaries (Tashkīl), leaving minimal resources for textbooks, teacher training, classroom materials, school repairs, or winter heating. The education budget exists solely to sustain the system administratively, rather than to ensure academic functionality.

The Report identifies several key challenges and reiterates ongoing concerns regarding access, exclusion, and declining quality. However, it primarily remains descriptive and does not address the deeper structural, institutional, and policy factors contributing to the crisis. By not confronting the political and policy roots of educational repression or offering a clear framework for solutions, it risks reinforcing the issue rather than fostering a meaningful discussion on how to protect and rebuild education in Afghanistan.